Cosa sta succedendo in Sudan – Parte 1

“Ci sono ammassi di corpi gettati nel Nilo, militari che uccidono i feriti o chiunque chieda aiuto, mentre la disobbedienza civile viene repressa nel sangue”. Queste sono solo alcune delle testimonianze raccolte negli ultimi giorni da chi è abbastanza fortunato (o sfortunato a seconda dei punti di vista) da sopravvivere al massacro perpetrato dai militari in Sudan. Anche considerando l’alto tasso di crudeltà al quale le guerre civili degli stati subsahariani ci hanno abituato dalla fine del colonialismo in poi, è molto difficile rimanere indifferenti a ciò che sta avvenendo ultimamente. Quella dei militari e della polizia è una vera e propria repressione sistematica di ogni forma di protesta, repressione che ha a capo il nuovo uomo forte del governo di transizione, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo noto come “Hemedti”. Ma come si è arrivati a tutto questo? Per cercare di fare chiarezza sulla situazione in Sudan dobbiamo tornare indietro di qualche mese, per la precisione allo scorso dicembre, all’inizio delle proteste.

L'ex presidente del Sudan ora deposto, Omar Al-Bashir

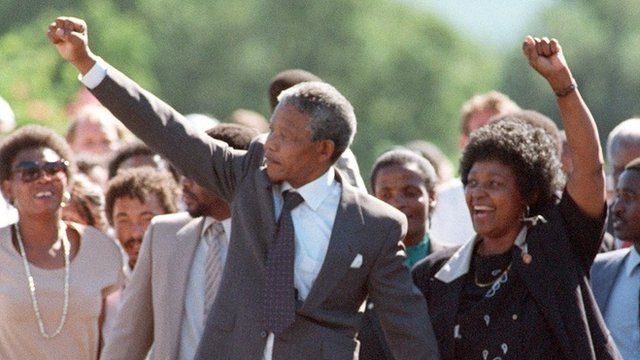

È il 19 dicembre 2018 quando in diverse città del Sudan si verificano proteste contro il trentennale governo dittatoriale di Omar al-Bashir. Le cause delle rivolte sono sempre le stesse: aumento del costo della vita, una burocrazia inefficiente al quale segue una corruzione dilagante e in generale un’arretratezza delle istituzioni, dovuta principalmente ai trent’anni di dittatura di al-Bashir. Inizialmente le proteste furono portate avanti, pacificamente, solo dai civili e lo scorso febbraio si arrivò ai primi arresti da parte delle autorità, con al-Bashir che gradualmente sostituiva componenti governativi e regionali con ufficiali dell’esercito. Quello stesso esercito che l’aprile successivo avrebbe preso le difese dei protestanti pacifici, facendogli da scudo contro le forze di sicurezza. Il 10 aprile ha quindi luogo un vero colpo di stato che si conclude il giorno dopo con la deposizione di al-Bashir e l’entrata di un “Governo Militare Transitorio” (TMC) che fin da subito non è visto di buon occhio dalle opposizioni democratiche.

Il nuovo capo dell'esercito, e de facto del TMC, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo detto “Hemedti"

Tra aprile e maggio si sono succeduti diversi negoziati tra il TMC e le forze d’opposizione democratiche, negoziati terminati brutalmente lo scorso 3 giugno con l’intervento delle “Forze di Supporto Rapido” (Rapid Support Forces, RSF) che hanno fatto strage di civili (almeno 118 morti), diversi feriti, nonché stupri. A distanza di appena due settimane, questo evento è già ricordato come “il massacro di Kahrtoum”. Al massacro le opposizioni hanno risposto indicendo uno sciopero di tre giorni, dal nove all’undici giugno, nel segno della protesta non-violenta e della disobbedienza civile. Oggi, almeno a parole, il TMC si è detto favorevole a riprendere i negoziati per un governo democratico, rilasciando il 12 giugno i prigionieri politici.

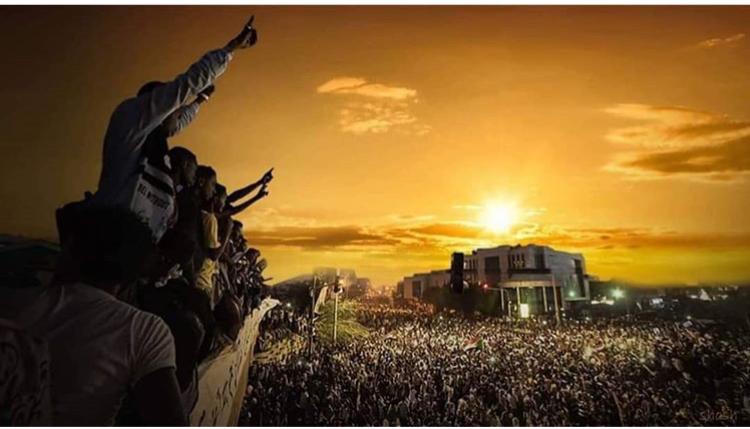

Che sia una manifestazione nelle strade o la "semplice" preghiera del venerdì, le proteste dei civili sono portate avanti sempre nel segno della non violenza

Sembra molto difficile però che il governo militare voglia seriamente impegnarsi nel rimettere il potere nelle istituzioni governative o almeno continuare sulla strada del dialogo. Storicamente non è praticamente mai successo che una giunta militare si sia fatta da parte a rivoluzione conclusa e non mancano esempi anche dalla storia recentissima, come in Egitto dove alla fine ha prevalso una giunta militare guidata dal comandante in capo delle Forze Egiziane, Al-Sisi.

Quello che però i militari stanno perpetrando in Sudan non è solo la “classica” macelleria da giunta militare ma porta anche i segni di un piano ben preciso e brutale per isolare il paese dal resto del mondo. Poco importa che l’Unione Africana abbia sospeso il Sudan dai tavoli congressuali, quello che importa è che i militari stanno tagliando i cavi di internet per impedire qualsiasi contatto con l’esterno; un’azione che, con i dovuti distinguo, ricorda molto l’opera di chiusura e isolamento portata avanti dagli Khmer Rossi in Cambogia negli anni ’70. Se questo isolamento si realizzerà o meno è ancora da vedere, ma certo è che le comunicazioni con l’esterno stanno diventando sempre più difficili. Alla luce anche di queste difficoltà (e brutalità) sono sorti molti account social (come Sudan Rise che vi consigliamo di seguire) per denunciare e tenere aggiornati su quanto sta accadendo in questi giorni nel paese.

In Sudan la rivoluzione e la denuncia delle violenze passano soprattutto dai social, a volte anche in maniera del tutto imprevedibile. La sera del 5 giugno stavo finendo di lavorare, quando, scorrendo tra le storie di Instagram, mi imbatto in quella di una mia collega accademica in cui condivideva a sua volta le testimonianze delle violenze del 3 giugno. Le chiedo come abbia fatto ad avere simili testimonianze e nel giro di un’ora entro in contatto, tramite una terza persona, con una studentessa sudanese, May, che mi manda video e foto, oltre a raccontarmi in tempo reale cosa stesse succedendo attorno lei. Le foto, che vi mostriamo nell’articolo, parlano da sole. Cosa invece May mi abbia raccontato sarà oggetto di un prossimo approfondimento.

English Version

What’s going on in Sudan

“There are masses of bodies thrown into the Nile, soldiers who kill the wounded or anyone who cries for help, while civil disobedience is bloody repressed.” These are just some of the stories collected in the last few days by those who were lucky enough (or unlucky depending on how you see it) to survive the massacre perpetrated by the military in Sudan. Even considering the high rate of cruelty to which the sub-Saharan states’ civil wars have accustomed us since the end of colonialism, it’s very hard to remain apathetic about what is happening lately. That of the military and police is a true systematic repression of every form of protest, repression which is led by the new strong arm of the transitional government, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo known as “Hemedti”. But how did we arrive so far? In order to shed light on the situation in Sudan we have to go back to a few months ago, last December, at the beginning of the protests.

It is December 19th of last year, when protests against the 30-year dictatorial government of Omar al-Bashir occur in various cities of Sudan. The causes of the revolts are once again the same: increase in the cost of living, an inefficient bureaucracy followed by a rampant corruption and a general backwardness of the institutions, mainly due to the thirty years of al-Bashir dictatorship. Initially the protests were carried out peacefully only by civilians and last February came the first arrests by the authorities, with al-Bashir gradually replacing government and regional components with army officers. That same army that the following April would have defended the peaceful protestants, acting as a shield against the security forces. On April 10th a real coup d’état takes place which ends the next day with the deposition of al-Bashir and the entry of a “Transitional Military Government” (TMC) which is immediately frowned upon by oppositions democratic.